Scala was one language that I played around with many years back (and blogged about then). Recently, I took the excellent course on reactive programming which rekindled my interest in Scala and I decided to brush up my knowledge on it as well as functional programming. I also happen to be reading what seems to be the best resource on functional data structures - Chris Okasaki's Purely Functional Data Structures. This blog is an introduction on how to implement some of those data structures in Scala. Since Scala is a general purpose programming language with an objective to fuse object oriented and functional programming, our implementation will follow that approach. It is also possible to do pure functional programming in Scala without bringing in object orientation, but that's not our focus here. So I'll call this implementation object-functional versus purely functional, but the properties are the same, the differences are only in the way code is organized.

Stack

We start with implementation of a really simple data structure. It is a container which supports the following operation:

cons: adds a new item to the containerhead: get last inserted itemtail: get rest of the itemsisEmpty: the container is empty or not

You can think of it as a cons list or Stack as Okasaki calls it. Before thinking about implementation, we can capture the behavior in a Trait like so:

|

|

Digression: Variance

In Scala, the type parameters are invariant by default, which means if you have a Stack[Shape], you cannot add a Circle to it though Circle is a subclass of Shape. For immutable collections it is better to have this behavior, so we need to make it covariant which can be easily done by adding a + to the type parameter. When you do that, Stack[Shape] will behave like a superclass of Stack[Circle]. But this also means that the following is possible:

|

|

This is clearly a problem so Scala compiler will prevent you from creating such an cons function. In the example above, cons should ensure that it only accepts a Circle or its subclass. This can be specified by constraining its type to [U >: T] where T is the type parameter for Stack. This is the intuition behind variance (we skipped contravariance) and if you are interested, read more here.

Armed with the idea of variance, we can make our Stack trait more general:

|

|

Implementation

One way to implement Stack is to consider two cases. A Stack could be empty or it could have a head and tail. Further, empty can be a singleton and we introduce an abstract class CList to represent this particular implementation:

|

|

Given this, one could create a Stack like:

|

|

Persistent

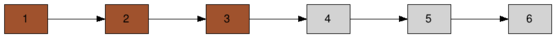

An important property of functional data structures is that they are immutable, any change on them would give us a new copy. This may not be as bad as it sounds since the structure can be often shared. For instance, if we have a list:

and we append 0 to it, we get a new list:

but the tail of second list is just a pointer to first list (in the image, only 0 is a new node as the color shows), so no extra space is required. If we insert an element in between, the elements till that needs to be copied but rest can be shared. If we append two lists, xs and ys, all elements in xs needs to be copied but ys can be shared:

++

++

==

==

There are ways to optimize this to minimize copying.

But keeping things immutable has many advantages. One particular benefit is even after updates the previous ‘version’ of the data structure is available since we don't modify anything. For this reason, functional data structures are also called persistent.

Other operations

The implementation we have so far is trivial and we can add other operations:

update: inserts an element at a given index.++: catenates two Stacks together

The implementation for this is straightforward. We just need to handle the two cases. Let's also add a toList function to convert this to Scala List for debugging.

|

|

Note that the update and ++ operations return a new Stack which potentially shares the structure of old Stack as we discussed before.

Digression: Testing

Now that we have written some code, how do we test it? We need to have some test data and unit tests for testing Stack. Also we need to test for Empty and Cons case separately. Instead of writing specific test cases, let's use Scalacheck. Scalacheck basically allows us to assert properties or invariants about the data structure and it takes care of generating random data for us.

Since we have a new data structure, which Scalacheck does not know about, we need to describe how to generate data. One way to do it is:

|

|

It might look a bit complicated, but all it is doing is describing how we can construct arbitrary Stacks. Once this is done, we can start writing our tests by just describing properties:

|

|

Note that we did not provide any sample CList. ScalaCheck will do that for us by testing with various randomly generated CList.

Exercise

Implementing a suffixes operation is provided as an exercise - given a Stack generate all its suffices. So suffixes of [1,2,3] should be [[1,2,3], [2,3], [3], []]. It has to be generating in decreasing order of size. Given our classes, this can be easily done:

|

|

and a simple test which passes:

|

|

That is all for a basic implementation of Stack. See the complete code for Stack and the test. We could add many operations like map, filter etc in a similar way. If you are interested, take a look a Scala's implementation of List which is more general and feature rich.